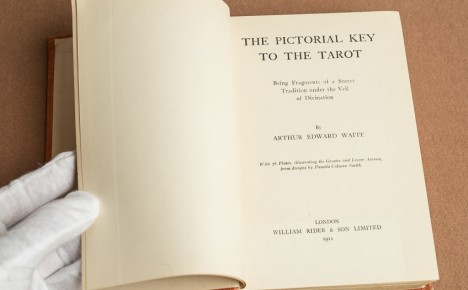

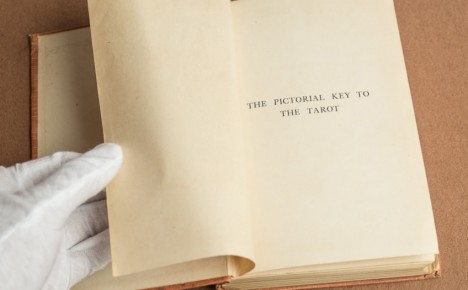

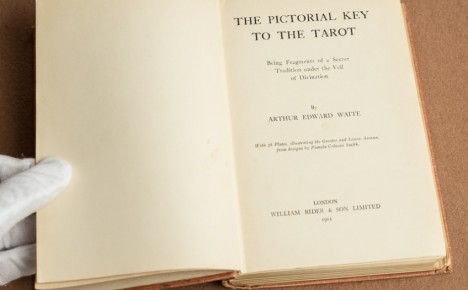

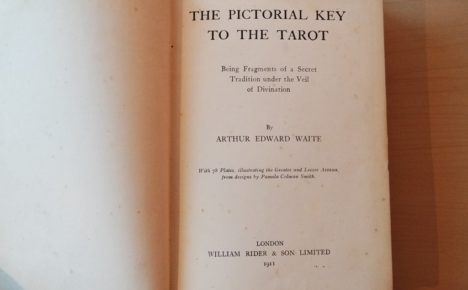

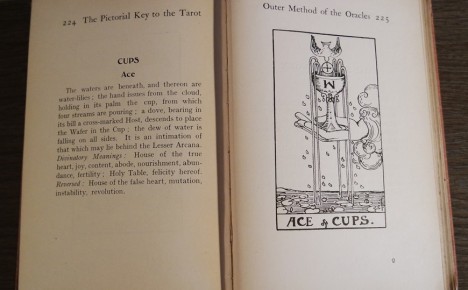

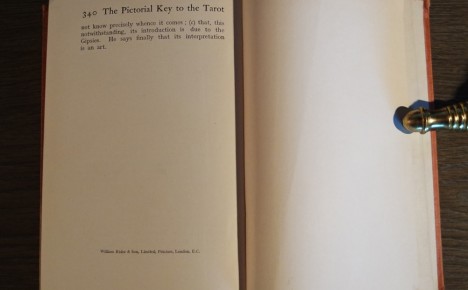

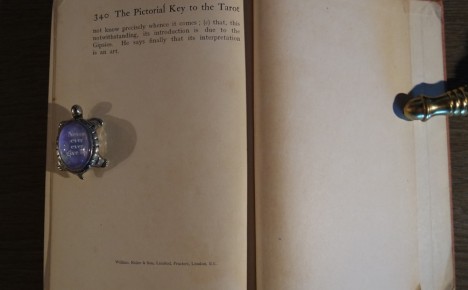

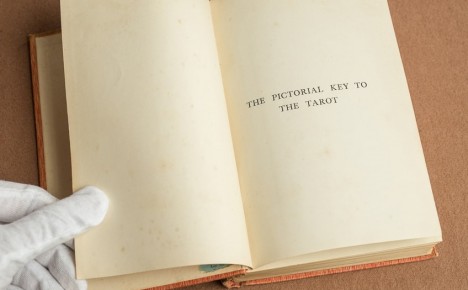

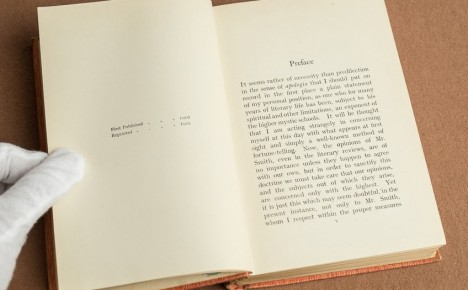

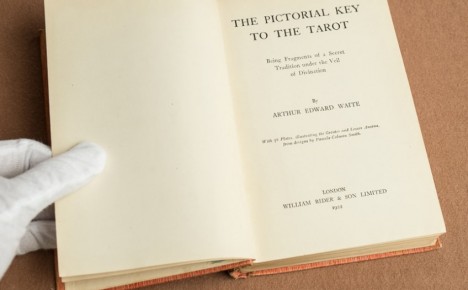

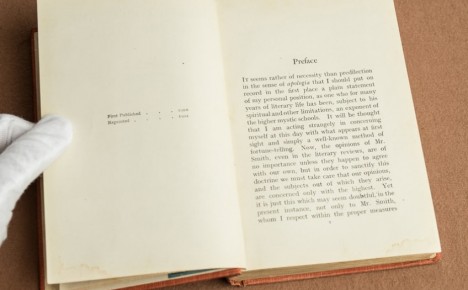

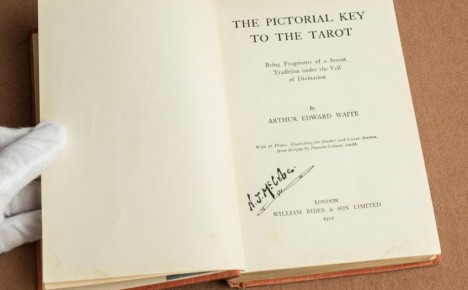

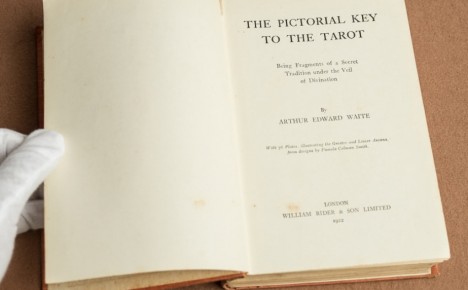

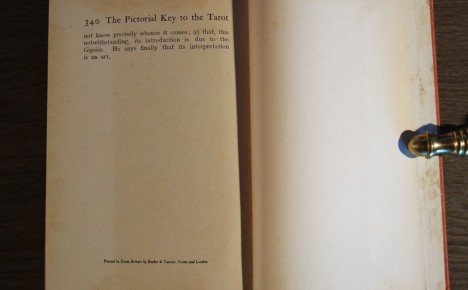

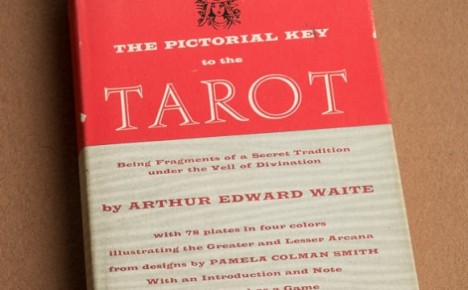

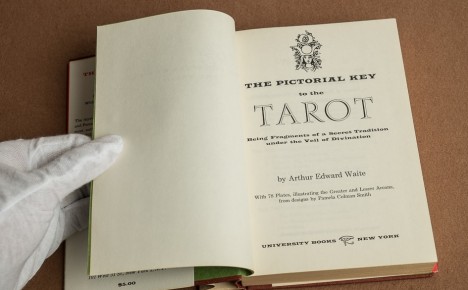

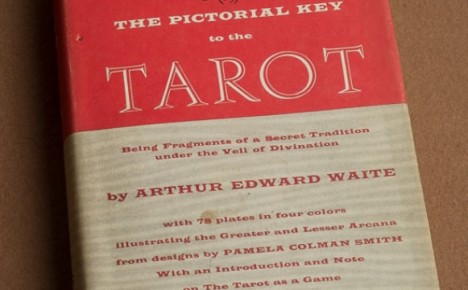

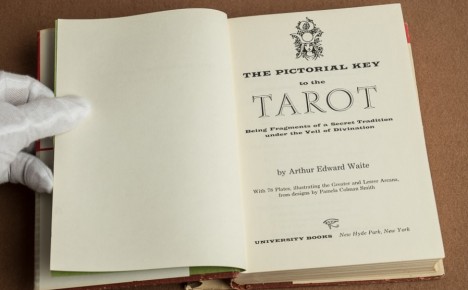

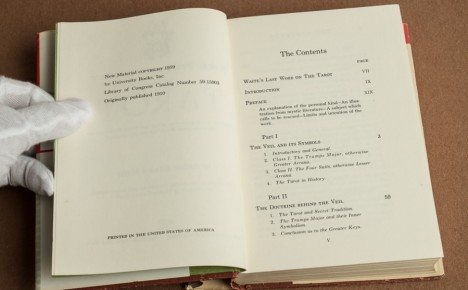

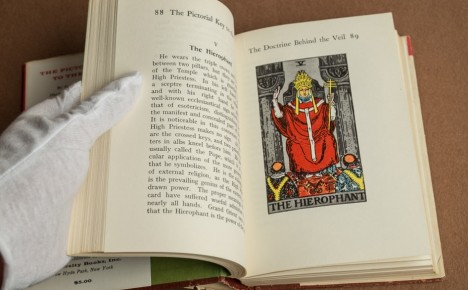

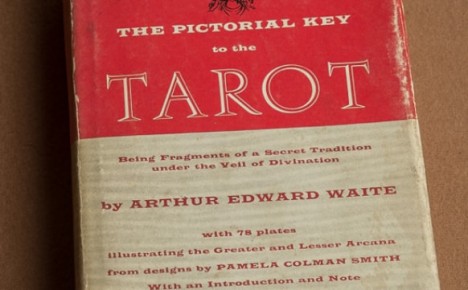

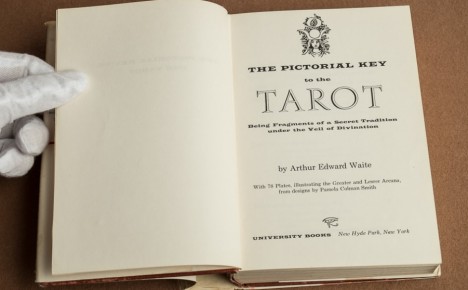

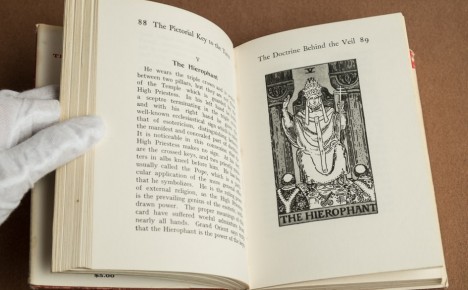

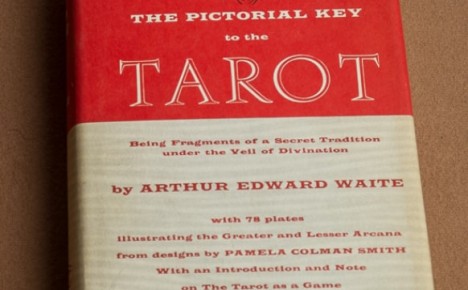

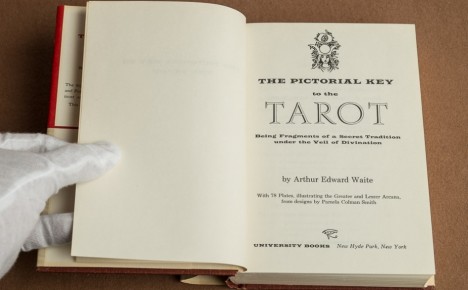

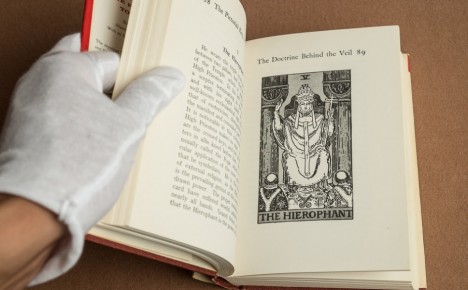

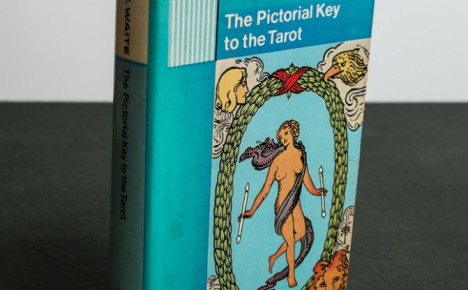

This is a republication of the 1910 Key to the Tarot (a.k.a. KtT), only “now with pictures!” The wording is the same but the pagination changes to make room for the images, which are unshaded black and white “line only” ink illustrations with borders of Pam’s art. Our working theory is that the The Pictorial Key to the Tarot (PKT or PKtT) was originally released in November 1910 with a pub date of April 1911. Here is the basis of that theory:

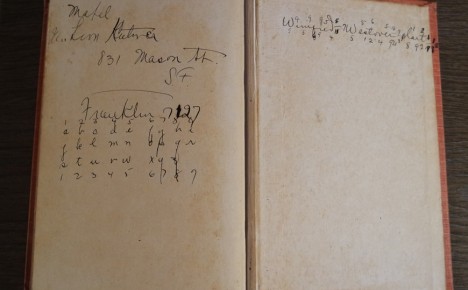

- I have a copy dated November 1910.

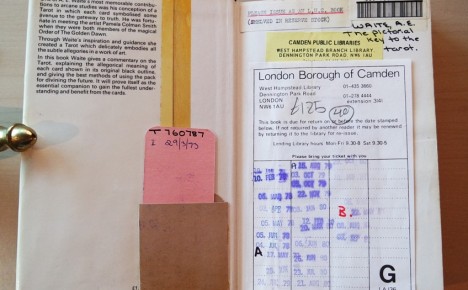

- Koretaka Eguchi has a copy with an advertisement included dated April (1911) and has a listing of books “ready in May,” that were released in May 1911. His copy has 48 extra pages of advertisements from William Rider & Son, Ltd.

- The November 1910 Occult Review (OR) stating the PKtT would be “ready early in November.”

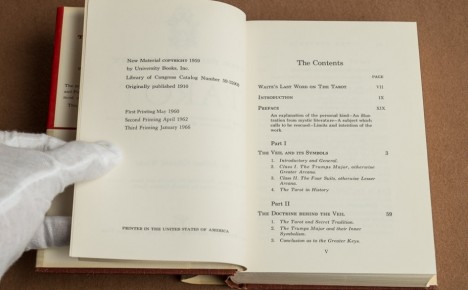

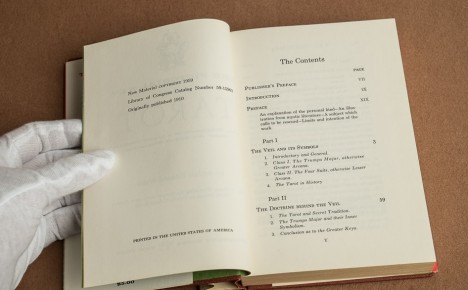

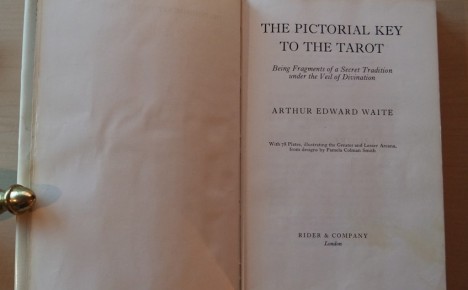

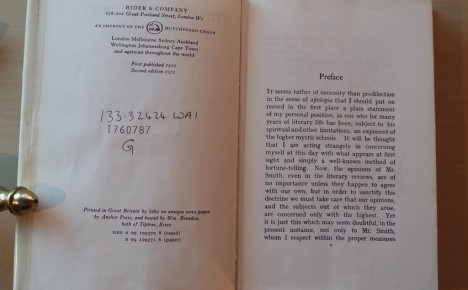

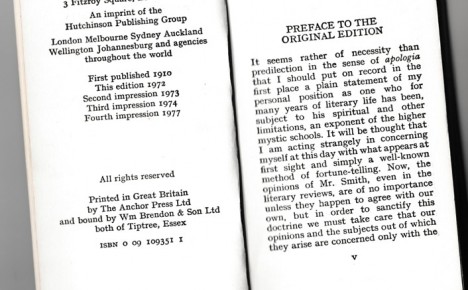

- The 1922 (2nd) edition of the PKtT states that it was first published in 1910 and again in 1922.

- The 1972 edition of the PKtT states that it was first published in 1910.

So I guess we can ignore the 1911 publication date printed on the title page of the first edition. At the moment this seems to be solid enough to go on without jumping to unfounded conclusions, but if we are corrected in the future (by the ghost of A.E. Waite for example) I will make sure this information changes.

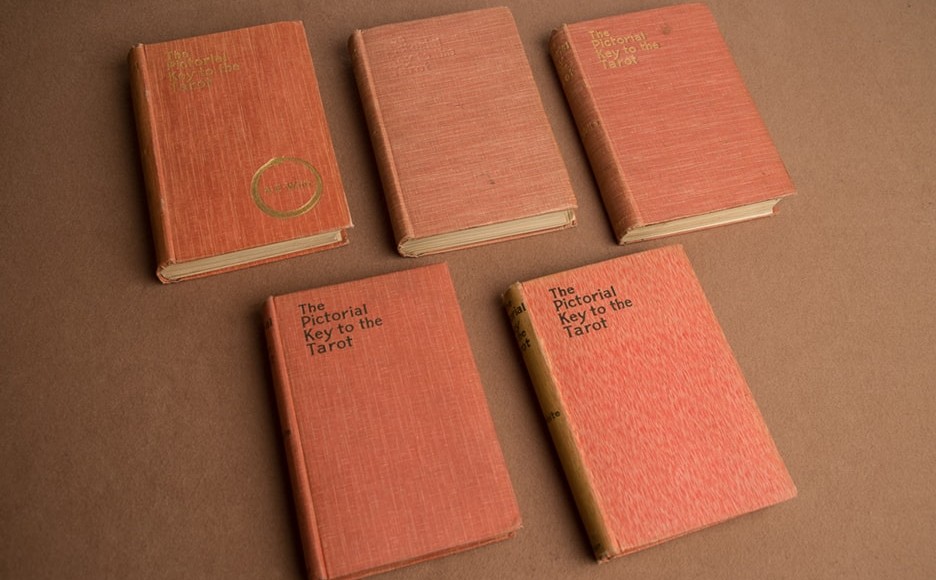

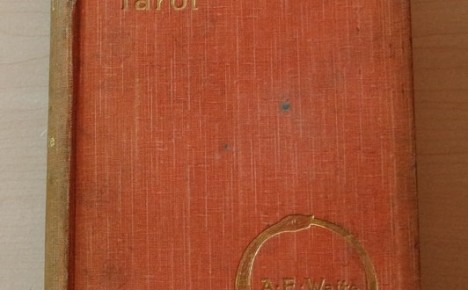

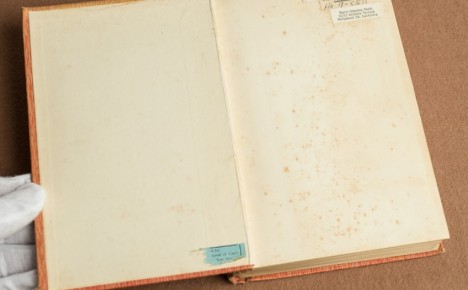

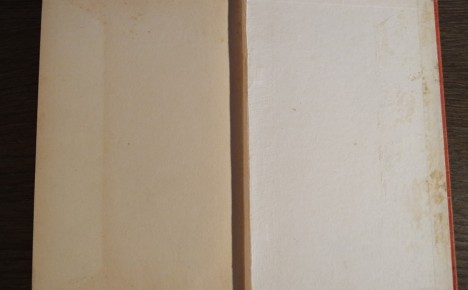

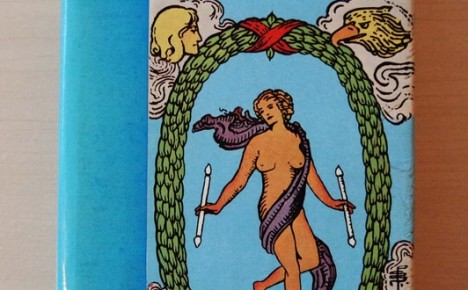

Now, as to the book format, the 1910/1911 versions are bound in orange cloth with a vertical grain while later editions change to a horizontal grain and later a strange effect you just have to see for yourself and decide what it means. This is one easy way of instantly telling the approximate year of publication just by looking at the cover. The first versions had gold debossed front cover and spine text, and also a gold ouroborous. At some point before the 1922 “second edition” the ouroborous was removed. This may coincide with the later printings of the unillustrated Key to the Tarot, as they were most likely printed at the same bindery (circa 1920). The die, or art, for the snakey may have been created by the first printer and not transferred to the new printer. The previous sentence was speculation, but we do know the various printers who printed the various Keys and Pictorial Keys, so this may have been a cost saving measure.

Still later print runs (still with the “second edition” 1922 copyright) used black ink on the cover instead of gold ink. These are undated but would most likely have been printed during WWII when there were shortages of all kinds. The last year Rider believes the original books were printed was 1939, so the black ink specimens that exist work well with that timeline. The dates on all Keys simply refers to the origin date of that particular version. No cards or Keys were marked by Rider for copyright until 1971. It will take a LOT of research, but British and American law point to these having been public domain for quite some time. When you count up the number of individuals and companies who have printed and published (for sale to the public) The Key to the Tarot, it is a commonly accepted fact; but don’t take our word for it. Ask your legal professional (this is good advice for anything to do with the tarot). For a complete list of credited and known printers of the tarot that Rider worked with please see this page. In the meantime, here’s is a partial list of who published The Key to the Tarot over the years (just below the galleries of PKtT images). Certainly many more will come along. Also, you can find the PDF version of the Key to the Tarot online in numerous places.